Capitalism and The Prisoner's Dilemma

How a simple thought experiment demonstrates the problem with free market capitalism

Upon first introduction, the prisoners' dilemma can come across as dry theory detached from everyday life. It is a thought experiment from the field of game theory, which is a branch of mathematics. Yet, the reason I am choosing to discuss the prisoner's dilemma is because it helps explains why so many things go wrong in society. Or more specifically, why free market capitalism never seem to work as well as promised.

It is a thought experiment which helps illuminate the two most central themes of political and ideological conflicts: The friction between individualism and collectivism. Or, to frame it in another way, should decisions primarily be made individually and independently of others or collectively through some democratic process aimed to maximize the benefit of that decision to the community as a whole?

Capitalism and socialism are exponents of these two ideological opposites. Proponents of capitalism favor individual decision-making above all else, while socialists will elevate democratic decision-making; meaning, there is a preference for society or groups of people making decisions together for common good.

To clarify, I am not in favor of any extreme outliers. I believe history has shown clearly that us humans thrive best on a healthy mix of individualism and collectivism. However, in this particular story, I am going to direct my criticism against favoring individualism and free market capitalism above all else.

Let me first explain the thought experiment before diving into a description of the wider implications to society, and how it helps us analyze flaws in free markets.

The Police Have Arrested Two Suspects

The thought experiment could be explained in numerous ways, but it is most commonly explained as the police having arrested two suspects for a crime. The police have minimal evidence. Only enough to charge both suspects on a minimal charge carrying a sentence of one year. Thus, the police are determined to get a confession out of the suspects.

As you have seen in countless American cop movies, they will rely on playing the suspects out against each other. They promise each one that they will get a reduced sentence if they snitch on the other guy.

More specifically, they offer a Faustian bargain, with different outcomes:

Case A – One suspect snitch on the other, while the other stays silent. The snitch gets released and the suspect who stayed silent gets 20 years of prison.

Case B – Both suspects stay silent and tell the police nothing. They both get the minor charge, as the police don't have enough evidence to charge them with anything more serious without a confession.

Case C – Both suspects snitch on each other and get five years of prison. It is reduced from 20 years because they cooperated with the police, but since they are actually proven guilty, neither can get released as in case A.

In the prisoner's dilemma, we formally call staying silent as cooperating, while snitching is referred to as defecting.

The optimal choice for both suspect collectively would be to stay silent (to cooperate). That will give a total of two years in prison. But staying quiet depends on trust. In the thought experiment, we are to assume the prisoners have no way to communicate and coordinate with each other. They have to base their decision entirely on their trust of the other guy.

If you are a sucker, you stay silent and the other guy betrays you and walks free. Thus, the safest strategy for two prisoners not trusting each other is to snitch on each other (defect). That gives each of them five years of prison. It is a much worse outcome than if both stayed silent.

For both to defect is what is called the Nash equilibrium, named after mathematician John Forbes Nash Jr (You may know if from the Hollywood movie A Beautiful Mind staring Russel Crowe).

A Trade Between Strangers

An alternative way of presenting the problem has been given by American scholar of cognitive sciences, Douglas Hofstadter. He chooses to explain the prisoner's dilemma as a simple game, or trade-off. One of several examples he has given is the "closed bag exchange":

Two people meet and exchange closed bags, with the understanding that one of them contains money, and the other contains a purchase. Either player can choose to honor the deal by putting into his or her bag what he or she agreed, or he or she can defect by handing over an empty bag.

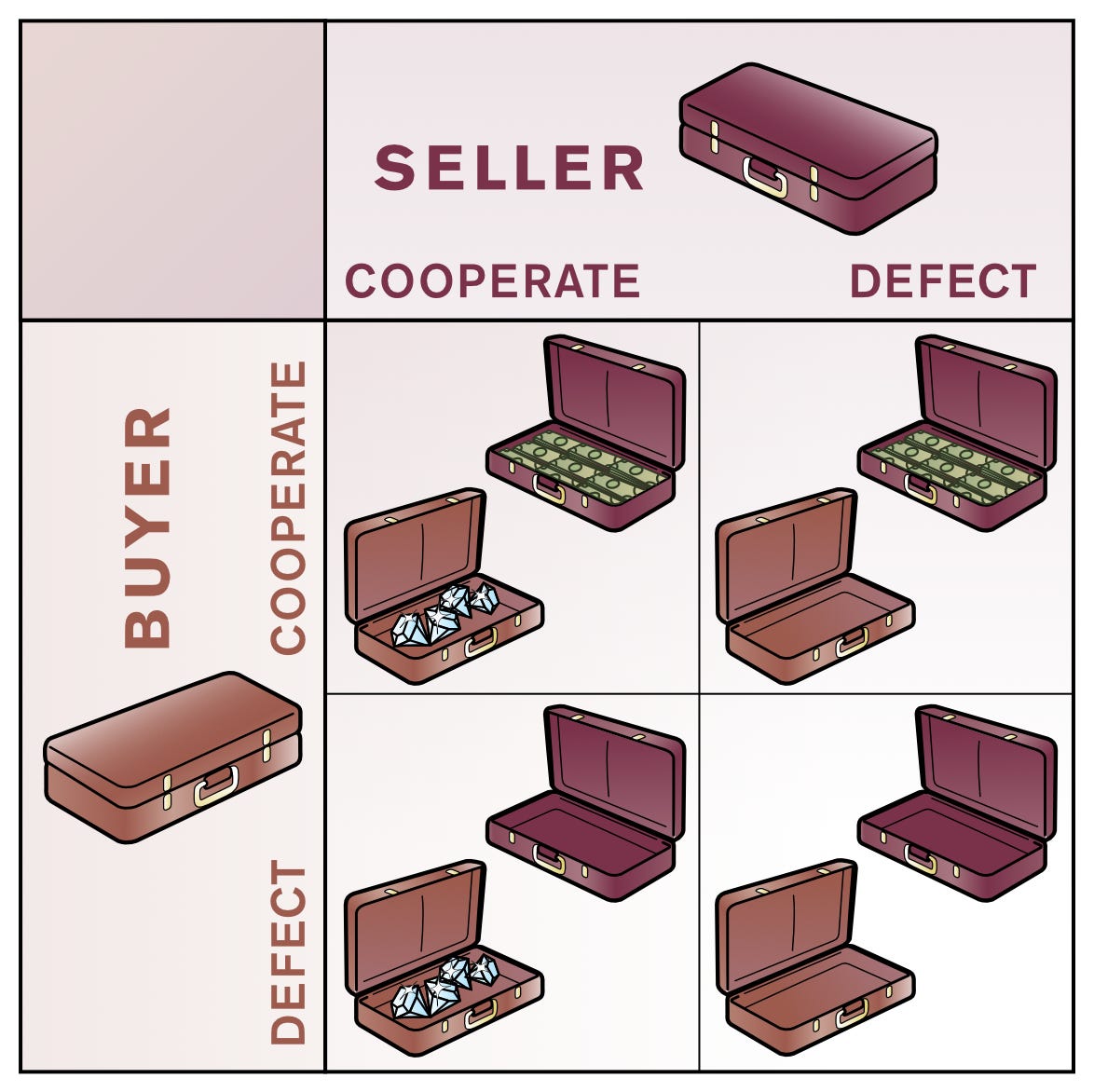

This trade-off is illustrated in the diagram below. It shows what the seller and buyer sees when they open their bags (or suitcases) after the exchange has taken place. For instance, the top-left quadrant shows the outcome when both buyer and seller honor the deal. The seller opens a suitcase full of money, which he received from the buyer. Meanwhile, the buyer discovers that the seller honored the deal because he finds a bag full of diamonds.

In the top-right quadrant, on the other hand, you can see the outcome when the seller screws over the buyer (defects). The buyer finds the received bag or suitcase empty, while the seller receives a suitcase full of money from the gullible buyer.

This same dilemma is frequently encountered by criminals engaging in drug deals. They might not get the drugs they paid for, or the drugs have been diluted with a cutting agent. You might have heard the expression: "The cocaine has been cut." It is a common scenario depicted in Hollywood movies.

Cold War Logic

There are many other examples of a prisoner's dilemma type of situation. The Hawk-Dove game tries to emulate Cold War logic. Should you cooperate and not build nuclear weapons, then both societies can then spend the saved money on education and public welfare instead. Alternatively, one power defects and conquers the "Dove" getting their resources. Or both defect, and you end up with WW3.

Notice in the diagram how the money has different labels. That is to show how a defecting player takes the money from the other country. For instance, when B defects, it invades country A and takes the money marked with an A.

Stag Hunt

There is even a stone-age style scenario called Stag Hunt. Two hunters can wait patiently at separate locations to bring down a large stag for mutual benefit. Alternatively, one of the hunters leaves their post to hunt a small rabbit that jumps past. The result is that they fail to take down the large stag, as that requires two hunters to achieve. The hunter that tried to cooperate has to go home hungry with no catch.

Hopefully, you get the general idea. Let us look at how this thought experiment can be applied to markets.

Application to Free Market Capitalism

One of the basic tenants of free market capitalism is the idea that through individual choice in the market, we will end up with an optimal distribution of scarce resources, whether that is consumer goods or capital.

It is often contrasted with the Soviet Union, which was infamous for having long lines of consumers competing to buy goods in limited supply. In the Soviet Union, prices didn't increase when consumer goods became more scarce. Hence, who would get a limited number of goods would be decided by whomever was willing to wait in line the longest, and not by whomever was willing to pay the most.

In a capitalist society, lines are eliminated by raising prices until people have to leave the line. That is because they can no longer afford to pay what is sold at the end of the line, or alternatively are no longer willing to pay the increased price. It is a fair system if you assume everybody has the same income and are of similar health and wellbeing. In this case, what you are willing to pay for something is just a reflection of personal preferences. John may be willing to pay more for a fishing rod than Tom because he likes fishing more, while Tom pays more for a bike because he prefers biking more. In a world with limited number of fishing rods and bikes, it means we are able to distribute these limited number of goods to the people who want them or appreciate them the most. To me, that sounds like a fair deal.

This analysis collapses once you make it more realistic by considering that people have very different incomes and physical needs. Because a rich healthy guy wants a private Jet, society allocates scarce resources to make that rather than say making medication to sick people who have lower income and thus cannot influence as strongly how society allocates resources.

Thus, it is obviously not an entirely fair system. However, one can still see how such an arrangement would cause increased production of things numerous people want and reduction in production of things people have become less interested in. In this sense, it seems like a flexible system that can adapt to changing preferences and needs of society.

The prisoner's dilemma, however, shows something entirely different. It demonstrates how the logic of individual decision-making, far from making optimal choices for society, can cause very wasteful allocation of scarce resources. Let me illustrate with a variety of examples.

Why is there so much advertisement?

It has been found that advertisement doesn't actually do that much to increase total sales in the market. Instead, what advertisement does is to pull consumer spending towards whatever company is having the most successful advertisement campaign. Often that simply means whatever company spends more money on advertisement.

Hence, advertisement easily develop an arms race logic. Say there is a market for 4 million cars in a country. Company A sells two million of those cars, and Company B sells the other two million. Now, company A decides to spend significantly more on advertisement and manages to grab a larger market share. Company A now sells three million cars while the competitor company B sells 1 million cars. Company B has to increase ad spending to bring its market share back to 2 million cars. Company A retaliates by increasing marketing further to gain back the market share advantage. Over time, none of the companies are selling any more cars, but they are both wasting an increasingly larger portion of their budget on marketing.

The irony of the situation is that no consumer in the market asked for more advertisement. Advertisement isn't actually satisfying the needs of anybody in the market. Advertisement isn't entirely useless. We require some information about product that are sold. However, in modern society this information is usually next to useless as marketeers have learned that being oriented towards factual and objective information doesn't sell well. Emotional manipulation of the primitive reptile parts of our brains works much better.

The excessive use of advertisement in modern capitalist societies is thus a case of the prisoner's dilemma. All participating companies are essentially defecting rather than cooperating for mutual benefit. It is not only reducing the bottom line of companies making different products and services, but it is also negatively affecting consumers. Watching your favorite TV show and getting interrupted by an annoying ad every few minutes diminishes the TV experience for the consumer. The consumer is getting a lesser experience. I am sure most of you have been annoyed at pop-up ads on the web.

Pollution and Global Warming

Why have we kept emitting ever more carbon dioxide to the atmosphere? We have known about the problem of global warming a long time. I am about to turn 45 years old, and I remember very well from elementary school in the 1980s that I was getting sick and tired of hearing about the greenhouse effect and global warming every week. Yet, despite being informed from childhood about this large and looming problem, my generation still failed to solve it. Emissions today are considerably higher than in the 1980s.

The underlying problem is that every factory has been making an individual decision. If you produce your products the clean way, then they will be pricier and you will lose out in the market, while the companies that chose to run on coal and oil will get the competitive advantage. In the prisoner's dilemma terminology, we could state that the companies being powered by fossil fuel are the defectors and those trying to run on green energy are those who try to cooperate.

Without coordinated action, you cannot solve a problem such as global warming. The most optimal individual and independent decision-making is to go with fossil fuels, even if it dooms society as a whole. The optimal choice for society as a whole can only be achieved through collective decision-making. Multiple companies and countries have to commit to similar restrictions and emission cuts. A valid alternative is to heavily subsidize clean energy, as to make individuals in the market pick clean energy for pure selfish economic reasons.

Poverty Reduction

Poverty like pollution is something that negatively affects all people in society, not just those who are poor. Poverty tends to drive crime, social dysfunction and drug abuse. More money has to be spent on courts, prisons, and police. We also miss out on a potential productive citizen contributing to society through taxes and valuable work contributions.

Thus, everybody would benefit from reducing poverty, but you end up in a prisoner's dilemma situation because it is tempting to not spend any money on poverty reduction and bank on everybody else spending money on it. The problem is that most people will think this way and thus only contribute minimal sums and efforts towards poverty reduction. Hence, highly capitalist societies always have significant difficulties with poverty, even if most citizens desire for it to not be there.

Individual decisions cannot solve the problem of poverty. One needs a coordinated effort by all of society, where everybody pledges to contribute. The normal solution is simply to use taxes to fund programs that help reduce poverty.

Employee Training

My next example was inspired by reading about the challenges of Japanese companies establishing themselves in the US. In Japan, companies spend considerable resources on training employees to a high skill level. That is one of the reasons why Japan has been able to dominate manufacturing and producing higher quality goods than other countries.

Employee training presents a prisoner's dilemma situation. Cooperation is required. If the corporation invests heavily in the employee, then the employee needs to stay in the company so that the company can reap the rewards from that training. A company not spending any resources on training in contrast can offer higher salaries. Thus, it may be tempting for a newly trained employee to defect and begin work at a higher paying company not offering any training.

Japanese companies establishing themselves in the US faced this problem. After they spent plenty of resources training employees, the same employees left immediately for higher paying jobs. To the Japanese managers, this was unfathomable because Japan is a loyalty-based society. Employees are not fired in bad times. Life-time employment has long been a feature of Japanese society. In return, employees are expected to stay loyal to their company.

American work-culture is the diametrical opposite. There is no loyalty in either direction. Employers are quick to throw their employees under the bus as soon as there is money to be saved doing so. Likewise, employees will quit on the spot if they can seize a better opportunity elsewhere. In terms of the prisoner's dilemma quadrants, we have a situation where both employee and employer are defecting. In Japan, we have the opposite: Employer and employees are cooperating. They are seeing a mutual benefit. Companies invest in the employee, and the employee stay with the company in good and bad times.

Thus, Japanese companies have struggled to establish high-skill manufacturing in the US. We can see how following free market capitalist logic to the extreme has detrimental effects. Always following the most selfish and optimal solution for the individual without concern for the whole of society leads to suboptimal outcomes for all of society. To be clear, I am not advocating the Japanese work culture. I just pick the US and Japan because they are convenient polar opposites to compare. I would probably favor a more moderate approach.

Reflections

I have given a few examples, but once you start looking at any society yourself, you will find that there are countless examples of the prisoner's dilemma in any free market economy. That I am critical of free market capitalism doesn't mean I want to abolish it. In public discourse today, people tend to be very tribalist. If you are critical of one system, they assume you are advocating the opposite system. In all my writing whether it is about economics, renewable energy or politics I tend to oppose beliefs in silver bullets. Workable solutions tend to be somewhat messy. Nordic social democracy is an excellent example. It is in my humble opinion the best political and social system ever devised. Yet as a system, it is neither fully market oriented nor fully socialist. Instead, it is a hotchpotch of ideas from liberals, socialists, and conservatives alike.

My aim with this story was to warn against the siren song of those who try to push the idea that markets are the solution to all our problems and the source of problems is always the government. Again, that should not be taken as an argument for having government solve everything. As I mentioned earlier, the Soviet Union had a very long list of issues, which had nothing to do with free market economics or capitalism.

But we must realize that many of the most important problems society face whether pollution or poverty requires people coming together and making decisions for common benefit rather than leaving all the decision-making to individuals not coordinating their efforts with anyone. You got to get people together and try to get them to find common ground. Markets don't work that way. You don't discuss with other buyers what is optimal for society. Instead, you just go and buy what you feel like. That works fine for buying a bike, but doesn't work for bike lanes. There are no stores which sell bike lanes to individual consumers. You cannot walk into a store and say: "I want Trek 5500 bike and 8 km of bike lane from my home to the office."

The latter requires collective decision-making. You must elect local politicians who through debate and discussion decide where bike lanes should be built to satisfy as many voters as possible. These kinds of decisions require an open debate with wide participation. You don't need to discuss with anyone what bike you want to buy. But building bike lanes or new subway stops in the city will require that a fair number of people engage in a public debate. That can be through newspaper articles, TV or town squares. It is a very different process from making a purchase decision in a market.

Based on your description of democracy I can't help but wonder what country you are discussing? You are definitely not talking about the United States. We live under a corrupt fascist oligarchy whose primary objective is constant war. Our media is populated by members of the security services. Our internet is censored. Members of congress are not permitted to write bills or offer amendments. Democracy requires free speech above all.

What is a "democratic decision making process?" Is that where we are permitted to send preprinted ballots through the mail to confirm a preselected member of the ruling class who will thenceforth make economic decisions on our behalf? Because if you think that is somehow democratic, then we have different definitions.

The free market allows people to make decisions for themselves. Everyone gets a vote at runtime. That is the only democratic decision making process I know of.