Collectivism in Nordics and Asian Compared

How do Nordic and Asian culture around individualism and common good differ?

Nordic societies are famous for social democracy, which is a social and economic model where the government takes an active role in ensuring the health and wellbeing of all citizens. In a corporate setting or in sports, the group is often emphasized over the individual; what did we achieve together rather than what did I achieve. It is a stark contrast to American rugged individualism, which much more strongly emphasize the achievements of the individual and where individual choice and freedom matters more than the well-being of everybody else.

Perhaps one of the best summaries of the Nordic ethos is given in the quote:

Nobody gets cake until everybody has had bread

– Einar Gerhardsen, Norwegian prime minister 1962

The emphasis on the collective well-being can seem similar to Asian culture, which is far more group oriented and less individualistic. An interesting experiment which showed this difference in a stark manner is the Michigan Fish Test carried out by Richard Nisbett and Takahiko Masuda in 2001 to compare American and Asian cultural differences. Nisbett presented subjects with a virtual aquarium on a computer screen.

"The Americans would say, 'I saw three big fish swimming off to the left. They had pink fins.' They went for the biggest, brightest moving object and focused on that and on its attributes," Nisbett explains. "The Japanese in that study would start by saying, 'Well, I saw what looked like a stream. The water was green. There were rocks and shells on the bottom. There were three big fish swimming off to the left.'"

In other studies, Nisbett discovered that East Asians have an easier time remembering objects when they are presented with the same background against which they were first seen. By contrast, context doesn't seem to affect Western recognition of an object.

In other words, Americans focused on individuals, the big fish, while the Japanese focused on the environment and interactions between all its members.

Another relevant example I remember reading about relates to South Korean PC bang, a type of LAN gaming center in South Korea, where patrons can play multiplayer computer games for an hourly fee. At these gaming centers it would become very popular with complex cooperative games where large number of players would form whole armies competing against each other. These types of games never had much success in the West because everybody wanted to be the hero, while these kinds of games rely on everybody carrying out a specific role or duty to the benefit of the whole group.

The Nordic Collectivist Paradox

It is easy to assume that Asian and Nordic culture should have a lot in common. Yet, they are profoundly different. In fact, American and Nordic society have more in common. Thus, when comparing individualism and collectivism, there is clearly something more complex at play. For several years, I tried to make sense of this question. Depending what you choose to focus on, Nordic society can appear to be both fiercely individualistic or very group oriented. What helped me solve the puzzle was coming across the work of Dutch social psychologist Geert Hofstede. In 1965 Hofstede surveyed 117,000 IBM employees across the world. The goal was not to identify national characteristics. However, by chance he discovered that the best way to predict what attitudes and answers an employee would give was strongly correlated with their cultural background, or more specifically their country of origin.

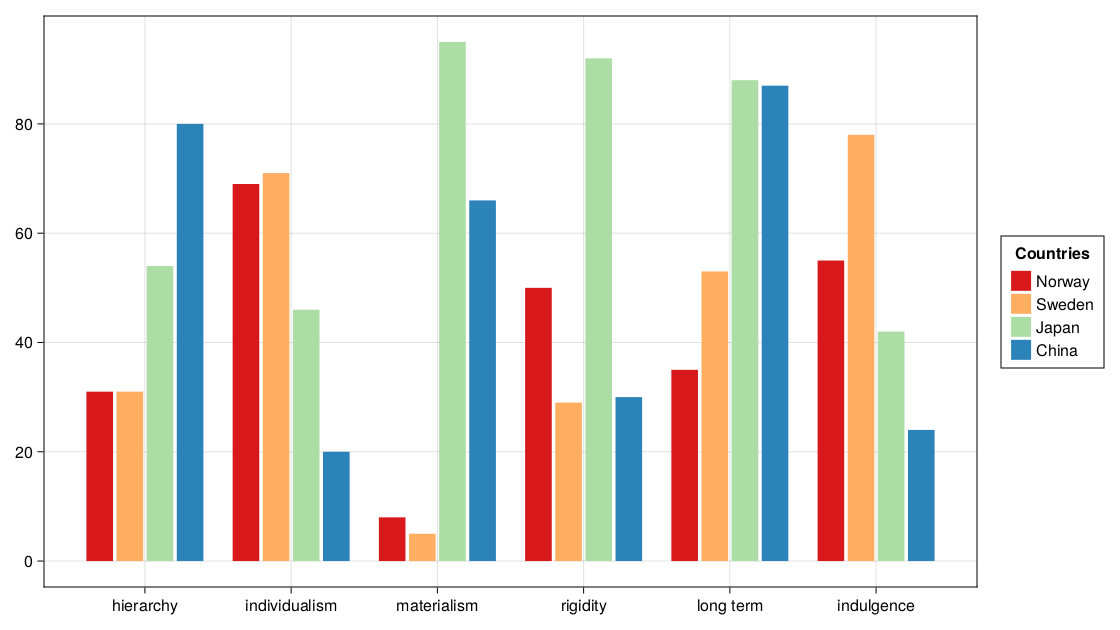

The work became the basis for Hofstede's cultural dimensions theory, which compares six national cultural preferences. I eagerly read the descriptions and plotted comparisons with various countries to see if they matched my own experiences living in different countries and interacting with people from different cultures. It convinced me that his approach gives an excellent picture of how countries compare in terms of values, preferences, and attitudes.

Asia and Nordics Compared Across Six Cultural Dimensions

I have chosen to label the cultural dimensions differently from Geert Hofstede because I find that people easily get confused by how he named them originally.

Hierarchy – How hierarchical is society? The power distance between boss and employee, parent and child, teacher and pupil.

Individualism – How important is an individual person seen relative to the group.

Materialism – Degree of preference for material reward and gain over quality of life. Also relates to focus on achievement and ranking over for instance cooperation and helping the weak.

Rigidity – The degree to which society has stiff codes of behavior and belief in absolute truth. The opposite is more acceptance towards different ideas. Behavior is less regulated.

Long Term – Delay short-term gratification for long-term gain. Propensity for thrift and saving rather than get-rich-fast schemes.

Indulgence – Propensity to spend money and time on leisure and fun. A low value indicates society practices stricter social norms.

In my plot I have chosen Norway and Sweden as proxies for the Nordics and Japan and China has proxies for Asian culture.

We can see from the plot that there are significant differences along several of the dimensions. Keep in mind when reading these plots that the values go from 0 to 100 and 50 means there is no specific preference for anything in that category. For instance, Norwegian society scores 50 on rigidity, which means Norwegian society isn't marked by stiff codes of behavior. On the other hand, Norwegian society is not seen as exceptionally open to new ideas, either.

To understand the metrics better, it is useful to add the US, which one of the best known cultures in the world thanks to the dominance of American media and pop culture all over the world. You will notice that America scores much more similar to Nordic countries. This is not surprising, given that both the US and the Nordics are part of Western culture.

Let us do some analysis of similarities and differences for related cultural dimensions.

Hierarchy and Individualism

Western societies tend to differ from other societies in that they have flatter hierarchies and more individualism. Here you can see how America and Nordics are very similar. In fact, contrary to what I was hinting at, at the start of this article, Nordic people are not very collectivist but highly individualistic although not as much as Americans. Although it would have been surprising if Nordic people were, given that Americans are world-famous for their individualistic attitudes.

China scores a mere 20 on individualism, which is very low. That is as expected. China is a highly collectivist culture, where people act in the interests of the group and not necessarily their own personal interests. In-group considerations affect hiring and promotions, with closer in-groups (such as family) getting preferential treatment. Employee commitment to the organization (but not necessarily to the people in the organization) is low. Whereas relationships with colleagues are cooperative for in-groups, they are cold or even hostile to out-groups. Personal relationships prevail over task and company.

What is perhaps more puzzling is that Japan scores 46 on the Individualism dimension. That is close to 50 which suggests Japan is neither particularly collectivist nor group oriented. That goes against a lot of our perceptions of Japan and thus needs further explanation.

Certainly, Japanese society shows many of the characteristics of a collectivistic society: such as putting harmony of group above the expression of individual opinions and people have a strong sense of shame for losing face. However, it is not as collectivistic as most of her Asian neighbors. The most popular explanation for this is that Japanese society does not have the extended family system, which forms a base of more collectivistic societies such as China and Korea. Japan has been a paternalistic society, and the family name and asset was inherited from father to the eldest son. The younger siblings had to leave home and make their own living with their core families.

One seemingly paradoxical example is that Japanese are well-known for their loyalty to their companies, while Chinese seem to job hop more easily. However, company loyalty is something, which people have chosen for themselves, which is an Individualist thing to do. You could say that the Japanese in-group is situational. While in more collectivistic culture, people are loyal to their inner group by birth, such as their extended family and their local community. Japanese are experienced as collectivistic by Western standards and experienced as Individualist by Asian standards. They are more private and reserved than most other Asians.

But how do we explain Nordic individualism? The clue is in the exceptionally low score on Materialism. Geert Hofstede labels this as masculine vs. feminine values. A high scores indicate preference for masculine values such as heroism, competitiveness, assertiveness, and material reward for success. A low value indicates a preference for more feminine values such as caring for the weak, cooperation and quality of life. Countries with more feminine values would typically emphasize things such as welfare states more, have generous maternity leave, child care subsidies, more vacation and better work-life balance.

In other words, what may seem like collectivism in Nordic society is more about cooperating for common good. Extended family and personal networks are not vital in Nordic society, like in China. The welfare state is impersonal. It helps everyone, regardless of the relation people may have to each other. The group emphasis at a Nordic workplace is project and task oriented. When Nordic employees emphasize the group and what they achieved more than Americans, it is still related to individualism because the group isn't defined by personal relations or family ties. The group only exists in a professional setting.

In this regard, Nordic collectivism is more like that of Japan. In so far as people form groups and emphasize a group, it is groups individuals have chosen or which exist in a professional sense. They are not deeply personal groups of, related by blood. In other ways Nordics are thoroughly different from Japan as Japan has very high score on my materialism metric. In this case, the word "materialism" is a bit of a misnomer, as it really related more to the very masculine values of Japanese society. Prestige and rank matters much more in Japanese society than Nordic society. We can see that also reflected in hierarchy. Japanese society have strict hierarchies, while Nordic society has very flat power structures.

Let me elaborate on power differences and hierarchies because here I think there are many interesting differences. You can notice that the US for instance has a higher score than Nordics. There is an American YouTuber named Andrew Austin teaching in Sweden, who details numerous cultural differences between the US and Sweden. In this video, he mentions differences in view of authority. Teachers and students are on a much more even level in Sweden than in the US. In the US, a teacher has more authority. You address a teacher more formally by their the last name, while in the Nordics you address just about everybody by first name.

Famously, the Norwegian prime minister, Gro Harlem Brundtland, frequently insisted she'd be addressed as Gro rather than Mrs. Brundtland or Mrs. Prime minister. This kind of differences is replicated across society. Nordic parents will pay more attention to the wishes and opinions of their children, while in other cultures, a parent is more likely to expect to be obeyed.

The flat power structures are also reflected in a corporate setting. I remember a funny story from a tech company in Kongsberg, Norway. They didn't really have titles or any clear management hierarchy among all the various engineers. Yet, the lack of formal titles and hierarchy created problems when on assignments abroad with customers. The Norwegian boss then just decided to let each employee pick whatever title they felt they needed to get the job done abroad.

The lower power hierarchy in the Nordics can have both positive and negative effects in my experience. On the positive side, it means even people in junior positions are taken serious and listened to. There is a lot of autonomy for individual employees. On the flip side, it can sometimes be hard to determine who exactly is in charge and calls the shots. Occasionally, one can get paralysis in decision-making because nobody wants to impose their view on others.

I have personally seen how this can get problematic when Norwegian companies outsources to Asian countries. Employees in Asian countries are used to an assertive boss who says exactly what he wants. A Norwegian boss in contrast will give a vague description of what he wants and expect the employee to fill in the blanks and take initiative and use common sense when needed. In Asia in contrast, following the orders given by your superior to the letter is seen as important.

Norwegian management will thus frequently find themselves scratching their heads about why progress stalls over minor issues they are not used to dealing with. Let me nuance this picture a bit. Asian employees are generally more dedicated and putting in more effort to get the job done, while Nordic employees are more flexible in how they do the job. Ultimately, the issue is about cultural barriers, which is why Geert Hofstede stressed the importance of understanding different cultures. Cultural understanding matters a lot when doing business across borders.

Once working on a video conference system, we did not take cultural differences into account. The software was set to highlight whoever was currently speaking. However, when selling the software to China, it became clear that the biggest image had to always focus on the boss of the company and not whoever was currently speaking.

Materialism and Indulgence

Nordic and American society are much more similar in terms of indulgence than Asian societies. However, the nature of this indulgence differs. I noticed this difference very well when I lived in the US. Both Nordic people and Americans like to enjoy themselves and satisfy their desires without waiting too long. That differs from Asian societies, which are more constrained and focused on practical needs.

America is all about work hard and play hard. American materialism dictates that you work hard to make a lot of money, which you can then spend on "stuff." Americans will want the biggest house, the coolest car, the biggest stereo or visit the most awesome theme park.

Nordic indulgence is much more focused on leisure time. Nordic people would rather go on vacation, go skiing, hiking, hang out at their cabin or enjoy good food or a drink at a café or nice restaurant. For instance, when I was a student in the US my American friends would often work in the vacation to make more money to buy new cool stuff. I would instead spend that time to travel and see new things.

You can see that China scores even higher on materialism than the US. It is not a very leisure oriented society and not necessarily about shopping all the time like the US. However, the Chinese will buy luxury articles that convey status and success. Here one can see a clear difference with Nordic society. You may have noticed that Nordic design as seen in IKEA furniture, Volvo or SAAB cars tends to emphasize simple clean lines. Nordic stuff is not particularly luxurious. Luxury plays a much more important role in the US and China. Both in China and the US, demonstrating material success is typically seen as important.

I remember female colleagues who had studied in the US referring to their dating experience. They remarked in particular about how American men were very eager to talk about how much money they earned and their material possessions such as summer houses and cars. In the Nordics, bragging about material possessions would come across as rather distasteful.

High-end luxury stories in Oslo, where I live, actually sell primarily to Chinese tourists, not to native Norwegians. Despite Norway being wealthy from oil money, it doesn't look anything like Dubai or Abu Dhabi. There are few super-expensive luxury cars such as Bentley, Bugatti, Rolls-Royce or Ferrari. Nor are there many huge, glitzy high-rise buildings trying to beat hight records.

Interestingly, one can notice that Volvo after being taken over by the Chinese have become much bigger and more luxurious.

Long Term vs. Short-Term Perspective

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Erik Examines to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.