How Did Printing Work in the Time of Gutenberg?

An explanation of printing jargon such as punch, matrix, and type

When reading about printing in the time of Gutenberg on wikipedia, it can be hard to understand the terminology. Personally I was confused by the word matrix. Many of us will associate the word matrix with a lattice or table of some sort composed of many elements. I was confused by the image blow, showing a composition case. Because the case contains many elements, I got into my mind that this whole thing was a matrix. That is wrong. Each individual mould of a letter you see in the case below is what we call a matrix.

A matrix represents a single character, not multiple. Why not call it a letter mould and avoid confusion? A matrix isn't a full mould. It only gives the shape of the letter. If you look at actual types shown below, you can see they are like long square rods. Gutenberg would combine the matrix with a hand mould to create the whole mould for a type. Next he would pour a liquid metal alloy consisting of lead, tin, and antimony into the mould. The alloy cools quickly, and out comes a lead type similar to the ones seen below: Square metal rods with typefaces on them.

We must also appreciate that printing technology has evolved a lot over the years. The composition case I showed was not used by Johannes Gutenberg. It got used from the 1950s in what we call hot metal typesetting. Gutenberg would have typeset pages by composing movable types on a composable stick, as shown below.

Next the metal types would get inked with ink balls. Once the surface of all metal types are covered in ink, a paper would be placed on top. The paper is secured in a frame, so it doesn't move around. A screw press is then used to press the paper against the metal types with great force. The pressure causes the ink to get imprinted on the paper.

Relation Between Punch, Matrix and Type

A type can be made in many ways. Initially, the Chinese would carve out a type from wood, rather than using metal. There are a couple of problems with this approach: Wood wears out after a few times of printing, and it is slow to carve the same character over and over again. What we need is a quick way of duplicating characters we have carved out of wood.

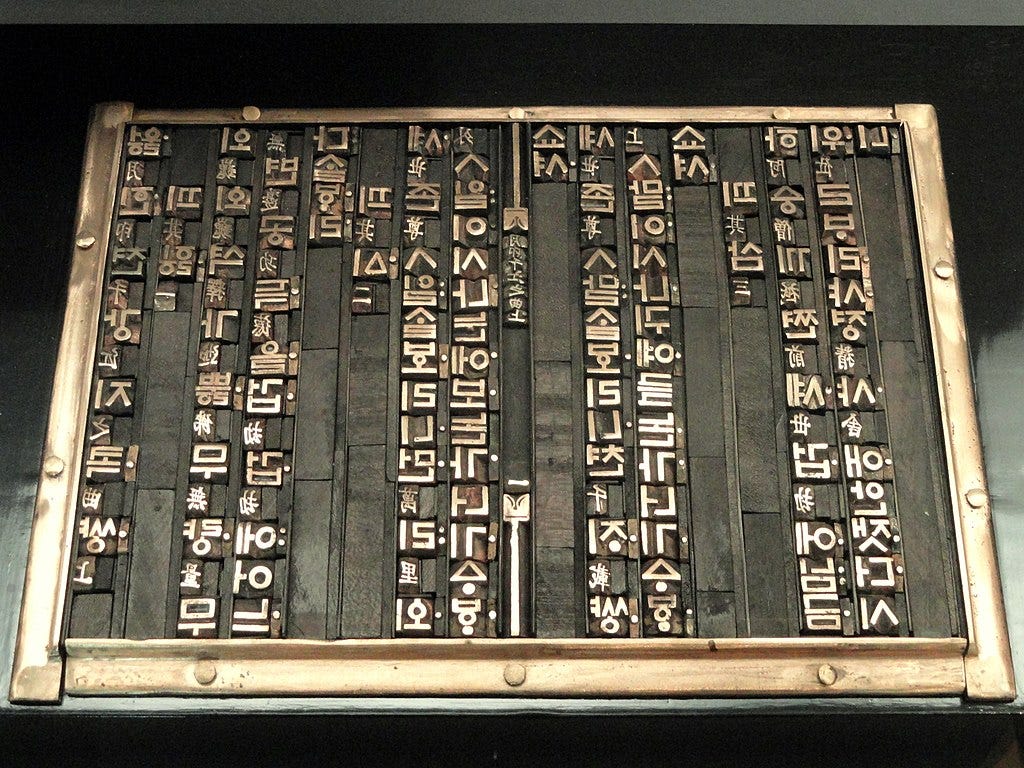

In the 13th century, the Korean came up with a solution. They would fill a box with clay and press the wooden type into the clay to create a mould. In printing terminology, we have used the wooden type as a punch and created a matrix in the clay. The box gets closed, and they would pour molten bronze down into an opening to create a bronze type (sort).

This printing technique was inspired by how bronze coins got minted in China. It allowed the mass production of metal types, which are more durable.

The Gutenberg printing technique replaces the punch with an iron type, the clay with bronze, and uses a lead alloy to create the duplicate. Gutenberg engraved each letter on a hard steel rod to make the punch. What benefit does that have? Instead of pressing types into clay, he would punch them into soft metal, such as copper. That left Gutenberg with a more durable matrix. With the matrix, a mould could be made, and lead alloy poured into to make duplicates.

When first trying to understand how this processes worked, I questioned the use of a punch. Why not carve the matrix directly? That obviously doesn't work in general. You cannot pour hot liquid bronze into a mould carved from wood. With the Gutenberg approach, you could in principle carve a matrix directly out of copper. However, there are numerous problems with this approach: You cannot test the shape of a mould quickly. A steel punch is the same as a type. You could put ink on it and press it onto paper to see that you get a letter that looks right. If it looks wrong, just continue filing the punch until it looks perfect.

The matrix only exists because you cannot use a type as a mould directly. Creating a matrix is one level of indirection to facilitate the duplication of a type you have made from solid iron or steel (the punch).

Summary

A page to print is composed of many types lined up, which get covered in ink. You could carve or file every type used in a page, but that would be time-consuming. The same characters will be used multiple times on a page, so we want a way to duplicate the types.

When using a type to create a mould to duplicate the type, we refer to the type as a punch and the mould as the matrix. We call it a punch because we literally punch the type into a softer metal to create the matrix. However, that is not the only approach. In Korea, types carved from wood would get pressed into clay to create a matrix.