Renewable Energy Powered the Industrial Revolution

Fossil fuel has been given too much space when discussing the forces driving the industrial revolution

There is a certain subgroup of people who are quite vocal about their opposition to renewable energy, and who have this odd habit of demanding that any advocate of renewable energy show their gratitude towards fossil fuels. Gratitude for what? The belief is that we live in modern society thanks to fossil fuels. Yet, there are so many false assumptions baked into this claim. Not to mention how many entirely write renewable energy out of the history books.

In fact, the modern world owes its existence to renewable energy. Let me give some background to explain why. The industrial revolution is considered to have happened between 1760 and 1830. The second industrial revolution happened from around 1850 to 1950. The factories of the First Industrial Revolution were almost exclusively powered by water power. I will quote professor Terje Tvedt at University of Oslo judiciously to make this point.

The role of and dependence on water can also explain the distinct regional patterns of England’s transformation in the late eighteenth century because industries (which were often clustered in combinations of textiles, iron, and engineering) had to congregate along streams and brooks.

Factories in Britain spread where there was water power to exploit. Mineral coal was not the driving force.

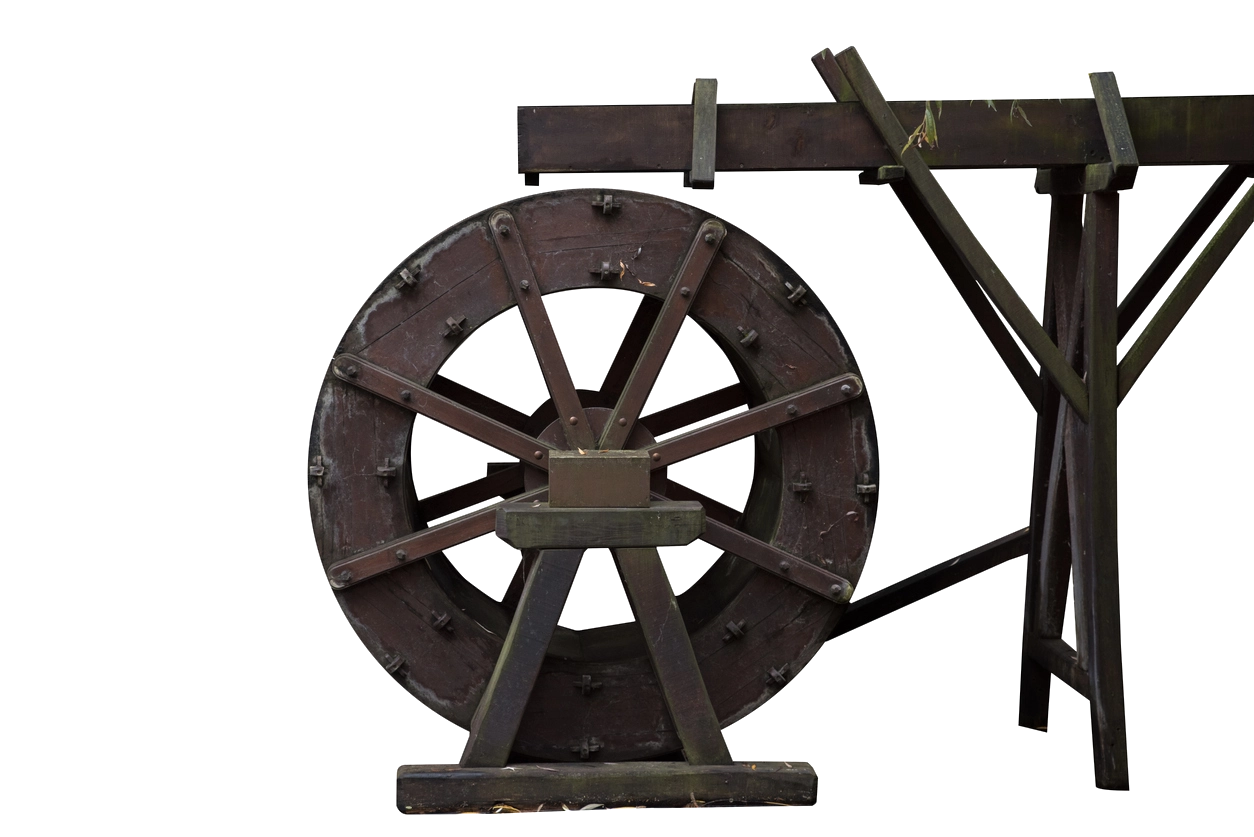

Conversely, no similar transformations took place in parts of England that lacked rivers and brooks with sufficient force to power water wheels, or where it was not possible to build dams, reservoirs, and manmade waterfalls that could drive these ‘water engines’.

That the heart of industrial England was centered around Manchester was no accident, but directly connected to the accessibility to water power in the surrounding area.

For example, it mattered that about 250 kilometers of year-round, ice-free, and stable rivers, streams, and manmade canals flowed through Manchester within 15 kilometers of the city centre. Some waterways, such as the Dene, Tib, and Corn Brook, important in previous centuries, have now been forced underground, while four rivers still flow visibly through the city: the Irk, Irwell, Medlock, and Mersey. It also mattered that the water ran down gentle hills, thus carrying sufficient clean energy to drive the water wheels.

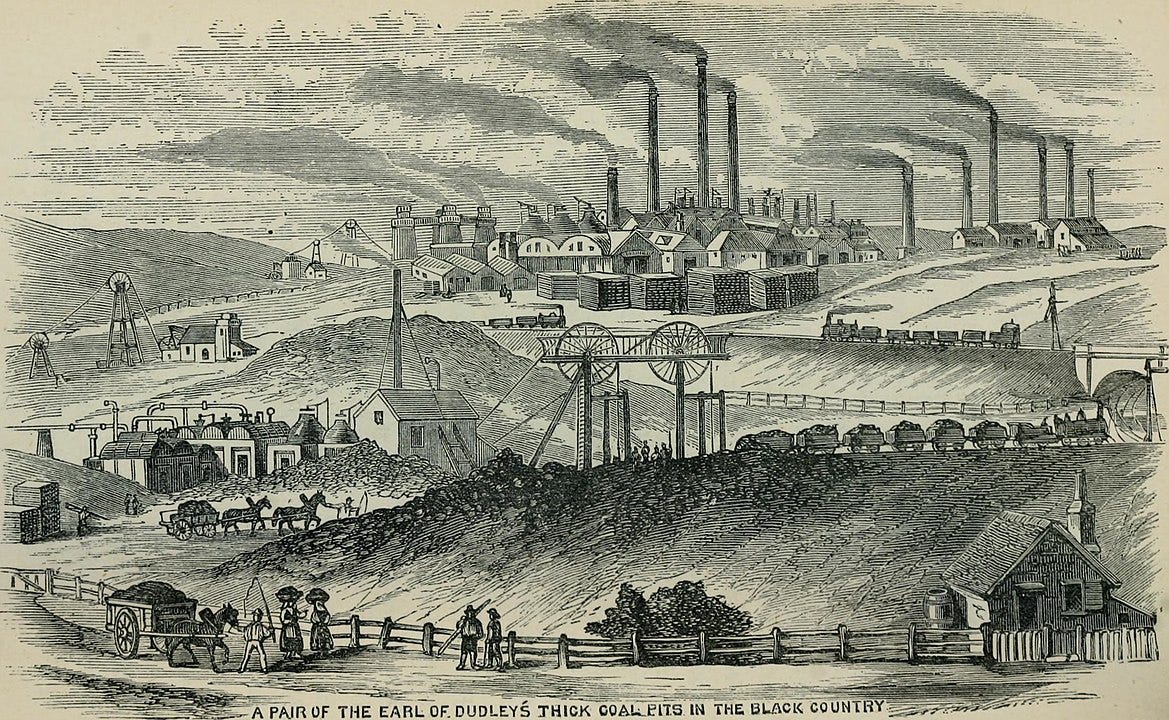

Where do all the images of tall chimneys spewing black smoke come from, then? The primary reason for that is that coke derived from mineral coal was used extensively in Britain for heating and iron production. The famous British Black Country gave an iconic image of the whole era. It was described by American writer Elihu Burritt as "black by day and red by night."

Coal is used to smelt iron ore and produce iron. It is used as what is called a reducing agent in a redox reaction. Yet, until 1709 when Abraham Darby established a coke-fired blast furnace in Britain, charcoal was primarily used for iron production. Mineral coal cannot be used directly in iron production. You need to turn it into coke. For this reason, charcoal as dominated through most of human history. Charcoal derives from wood and is not a fossil fuel.

Until 1850 all iron production in the US was based on charcoal

Despite Britain extensively using mineral coal, doesn't mean you have to. Britain began using mineral coal instead of charcoal because it becomes so deforested. Countries with far more forests such as the US continued to use charcoal. Until 1850 all iron production in the US was based on charcoal. The last steel mill using charcoal stopped operating in 1950.

Likewise, Swedish iron industry used charcoal for a long time. For instance, when Britain transitioned to coke fired puddling furnaces, Swedish mill owner Gustaf Ekman adapted the furnace in 1845 to use charcoal instead.

I am giving you all these details to hammer home the point that fossil fuel was in no way a requirement for the industrial revolution. The factories were powered by water, and charcoal drove the crucial iron making processes in many countries.

What about countries without rivers to exploit water power? The Netherlands kept adding windmills until around 1900. They had 9000 mills in 1850. And to quote low-tech magazine:

Germany had 18,242 windmills in 1895 (compared to around 18,000 wind turbines today) and Finland had 20,000 windmills in 1900. Portugal, Spain, several Mediterranean islands and many Eastern European and Scandinavian countries had many windmills, too.

Wind power was more than enough to push the Dutch economy high before any modern industrial revolution happened. The Dutch economy during the Golden age in the 1600s has short periods where it reaches GDP per capita of $5000. Great Britain doesn't reach this level until 1860. Germany doesn't get there until 1905, France not until 1909.

Switzerland is another interesting case. It grows rapidly from around 1870 to 1950. By 1909 it has surpassed Britain, and that is despite not having any coal deposits to power steam engines. Switzerland industrializes almost exclusively using waterpower. Water turbines got developed before mineral coal started playing a major role around 1820. First primitive electric generators began development in the 1830s. Already in 1866 we had electric generators suitable for industrial use.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Erik Examines to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.