The European Mill Revolution

Before the industrial revolution, there were windmills and waterwheels

Long before the industrial revolution with Spinning Jenny, James Watt and his steam engine, there was a mill revolution. One might call it a mini-industrial revolution. Windmills and waterwheels all over Europe were powering a large variety of mills.

This revolution began around 900 AD and was a uniquely European phenomena that would later have major repercussions in terms of European technological lead over other great civilizations. Terry Reynolds, the leading technological historian of the watermill, has contended that:

If there was a single key element distinguishing western European technology from the technologies of Islam, Byzantium, India, or even China after around 1200 CE, it was the West’s extensive commitment to and use of water power.

– Terry Reynolds, technological historian

Max Pfingsten gives some examples of how rapid the usage of mills grew in Europe.

In a single French province, watermill production increased from an average of a mill every 5 years (from 850-1080) to a mill a year (from 1080-1125) to 5 mills a year (from 1125-1175).

– Max Pfingsten, history instructor

After William the Conqueror had invaded Britain, he wanted a survey of everything that had come under his possession. In 1086 AD he had all of this info recorded in the oddly ominously sounding Domesday book. The book records 6,082 watermills in England. Let us put that into perspective. Early watermills, grinding grain, did the work of up to 60 men. That means the watermills in 1086 did the work of almost 400,000 people at a time when England had no more than 1.25 million inhabitants. That means doing as much work as almost 30 percent of the English population.

By 1500, the far more powerful overshot waterwheel became prevalent in Europe. Wikipedia has details on how powerful different types of mills were:

It has been estimated that the ancient donkey or slave-powered quern of Rome made about one-half of a horsepower, the horizontal waterwheel creating slightly more than 1.5 of a horsepower, the undershot vertical waterwheel produced about 3 horsepower, and the medieval overshot waterwheel produced up to 40 - 60 horsepower.

Low-tech magazine gives some numbers for the power of Dutch windmills, which suggest they were comparable to overshot waterwheels:

windmill constructed in 1648, showed that the mill generated around 40 horsepower at the windshaft but only 15.6 horsepower at the machines

Towards the end of the Dutch Golden age (1588 to 1672) there were 9,000 windmills in operation in the Netherlands, which must have significantly reduced the amount of work which had to be done by humans and animals. Keep in mind that the Netherlands in this period has from 1.5 to 2.0 million inhabitants. The windmills could easily have done more work than all the citizens could have done combined manually.

The number of waterwheels kept rising rapidly in the United Kingdom as well. It has been estimated that the United Kingdom had between 10,000 and 13,000 mills in 1300. All of Europe benefitted tremendously from wind and water power. From Low-tech magazine:

The total amount of wind powered mills in Europe was estimated to be around 200,000 (at its peak), compared to some 500,000 waterwheels

In short, there were a lot of mills in Europe, but what exactly were these mills doing?

Types of Mills and What they Did

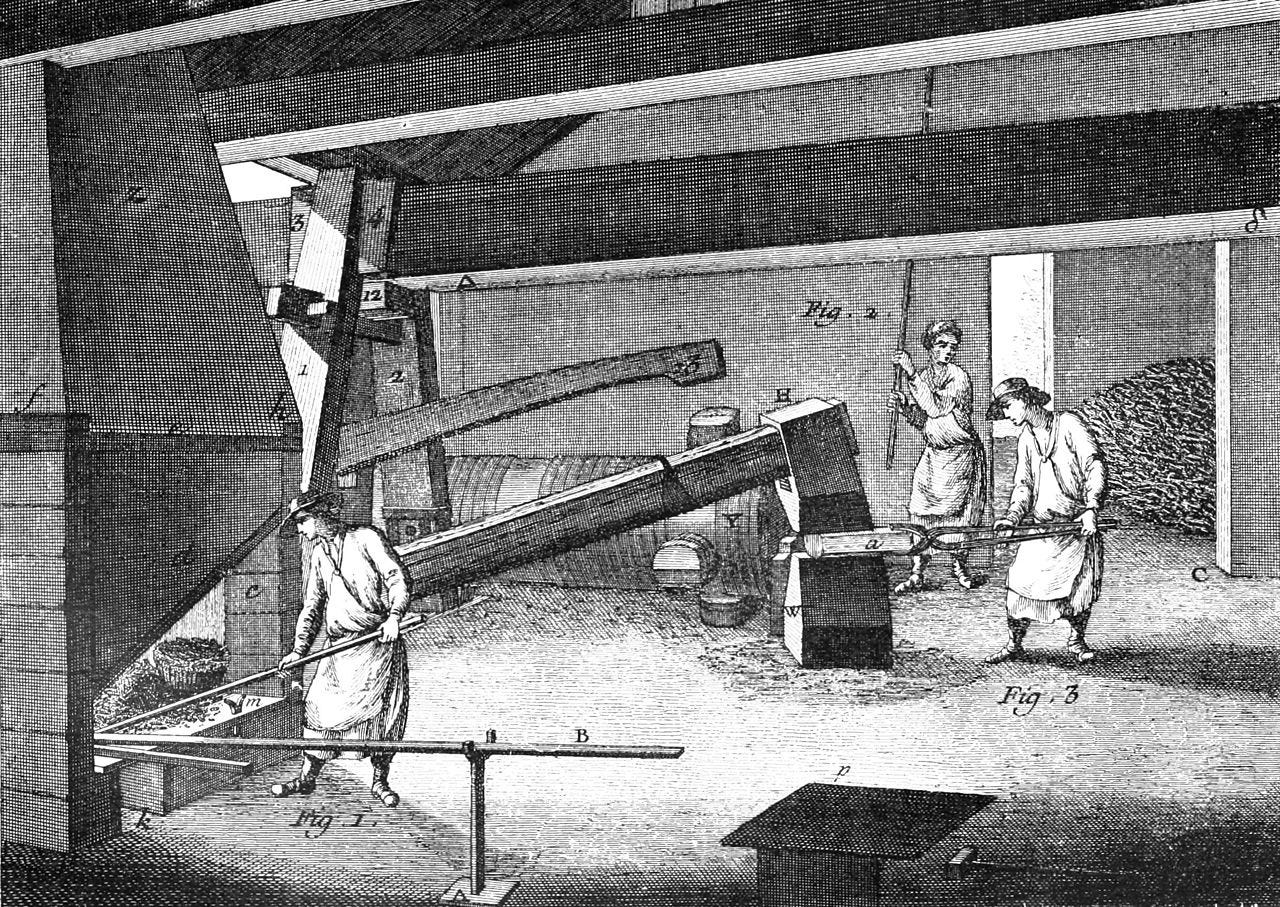

Today, we think of factories are things with complex machinery with numerous moving parts. Mills in contrast were quite simple. Mills were primarily designed to grind, crush and beat things, which doesn't sound very exciting and important. However, numerous important labour intensive processes require exactly those things.

For crushing, one places the millstones in a vertical position and create an "edge roller" following a circular path around a central axis. Grain needs grinding but a lot of other food processing needs crushing, such as producing olive oil by crushing olive seeds. The same technique can be used for: mustard, poppy seeds, linseeds, hempseeds, and peanuts. Linseed oil had important application in lubrication of machinery, guns, and weapon.

There are also numerous minerals and rocks which are useful to crush. Making gunpowder involves crushing sulfur and charcoal, for instance. Dyes are made from crushed minerals. The Dutch built hundreds of windmills in the West Indies for crushing sugar cane.

What about trip hammers? What can you use a triphammer for? You may have seen how a smith hammers iron on an anvil. Removing impurities from iron involves heating iron and knocking off the impurities, referred to as slag. This is a very labour intensive task which requires a lot of charcoal. With large trip hammers, one can work with large pieces of heated iron and knock out the slag much quicker, saving a lot of manpower and charcoal.

Traditional paper making is essentially about beating cloth soaked in water. The Netherlands used windmills extensively to produce paper . For literacy and the scientific revolution this was a crucial development as it allowed Europeans to make paper much more cheaply.

To get a sense of how labour saving mills could be, we can take an example from the fulling process. This is a process related to wool processing. Basically, you beat the wool soaked in water. Today, you could probably use a washing machine for much the same task. A fulling mill could in a couple of hours does what took 3 workers a whole year of hard work to accomplish. These facts give an inkling of why the Netherlands could be so much richer than everybody else.

The Dutch Windmill-Powered Economy

The Netherlands was a windmill powerhouse. Huge number of windmills were employed in all sorts of processing. Half the sugar imported to Europe got processed in the Netherlands. The Dutch didn't grow olives, but they crushed the seeds to make olive oil. Raw materials from all over Europe got imported to the Netherlands for processing and further export.

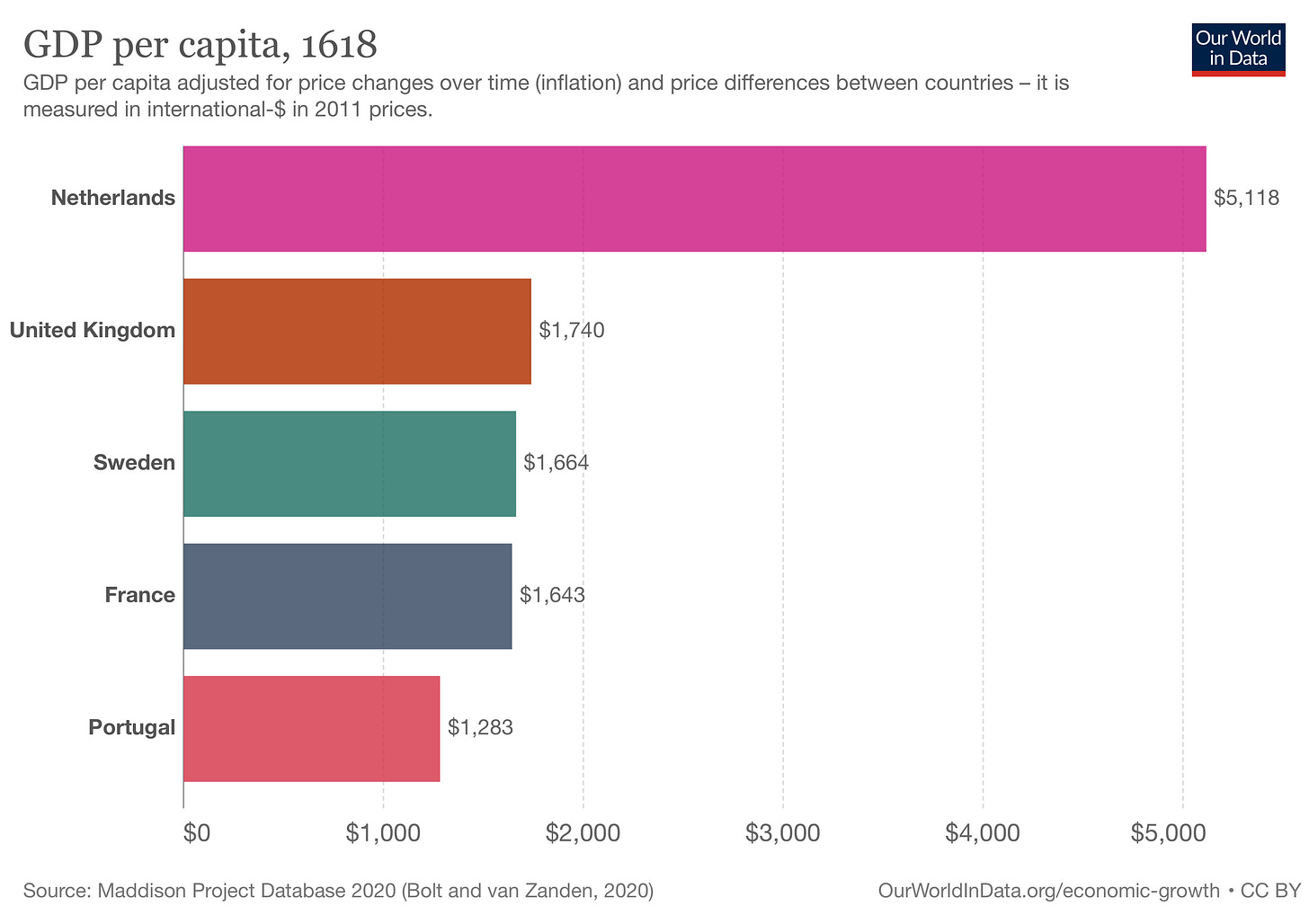

At their peak, the Dutch had a gross domestic product that was a staggering 4-5 times higher per capita than for most other European countries, China and India. The difference between the rest of Europe and the Netherlands was similar to the difference between the Netherlands and Indonesia today.

Perhaps an even more visible example of the implications of mills in the European economy is how windmills helped the Netherlands dominate seafaring and trade in the 1600s.

Let us put Dutch naval dominance in context:

In the 1600s the size of the Dutch merchant fleet probably exceeded the combined fleets of England, France, Spain, Portugal, and Germany

How could a country with such a tiny population crank out more ships every year than even huge empires? The Dutch had a trick up their sleeve: A wind-powered sawmill, invented by Cornelis Corneliszoon van Uitgeest in 1594. Low-Tech magazine gives more details:

The first sawmill ("Het juffertje" or "The missy") was built in the town of Zaandam by Cornelis Corneliszoon in 1596. By 1630, there were 83 sawmills north of Amsterdam, of which 53 were located in the Zaan district. The peak was reached in 1731 when there were 450 sawmills in the Netherlands, 256 of them in the Zaan district.

These sawmills powered by windmills allowed the Dutch to dramatically cut the amount of labour required to process wood for shipbuilding:

The importance of the wind-powered sawmill taking off in the Netherlands cannot be understated. Wood production didn't double, triple or quadruple; it grew by a factor of thirty, or 3,000%.

It was all in the time savings: Using the pit-saw method, sawyers could process 60 logs over a span of 120 days. Using a wind-powered sawmill, they could break down 60 logs in four or five days. What used to take four months now took less than a week.

The Dutch Zaan district was like a large industrial hub powered by a huge number of windmills, where wooden ships got built in a manner that looked a lot like assembly line production. Ships at different stage of assembly would pass from one station to the next, where a new team of specialists would perform tasks they were specialized on. Multiple ships at different stage of development would get worked on in parallel.

The Venetian Arsenal in the renaissance has by many been regarded as the first assembly line production, hundreds of years before Henry Ford. The Dutch took this a step further by using the inanimate power of windmills. The result was that countries all over Europe began ordering ships from the Netherlands. The Dutch were not merely transporting goods for other nations, but also buildings ships for them.

Final Remarks

The motivation behind this story was to give more background to help explain why a mill and machinery revolution did not happen in China before the industrial revolution. Before answering that question, we have to clarify that something significant was actually happening in Europe with water and windmills. They played a significant role in setting the stage for the later industrial revolution. However, the steam engine and textile mills of the late 1700s and early 1800s tend to overshadow the important developments that came before.