Why England Industrialized First

The forgotten role of water-power in causing the Industrial Revolution and why this uniquely benefitted England.

The cause of the Industrial Revolution and why it happened in Britain and not other advanced countries like China first, has been a debate for ages.

You have famous people such as Jared Diamond and Niall Ferguson, writing their own widely known books about this topic. You have historical figures such as Max Weber who popularized self serving notions of protestant work ethic.

Yet, there is one man, Professor Terje Tvedt at the University of Oslo and Bergen, which I really believe deserves more recognition in explaining how the world industrialized. Of all explanations I have read, I believe he has the most logical and compelling one.

Professor Tvedt is an expert on how water has shaped history and economy. More specifically how oceans, rivers and canals have helped power economic and technological development.

Tvedt has the excellent paper which will really open your mind, if you care about this topic: Why England and not China and India? Water systems and the history of the Industrial Revolution.

Here I will simply quote this paper, and add relevant notes to those less familiar with the topic. On page 43 we find this important paragraph:

Indeed, steam engines could not have been built in the first place without water wheels to drive the machinery that was needed to smelt the iron and form the cylinders that the steam engine was made of.

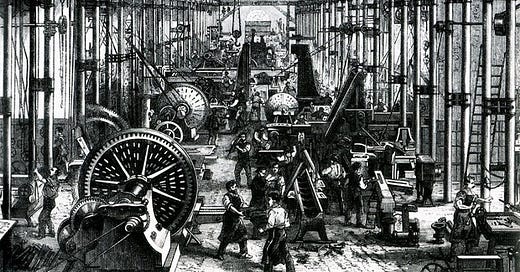

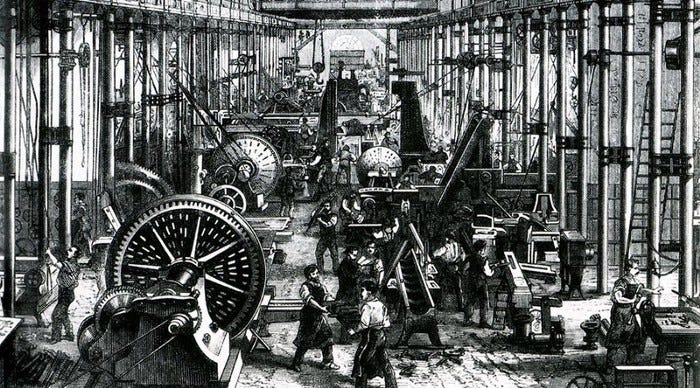

The development of the iron industry was crucial because it allowed the production of most of the machine equipment required by other industrial activities, whereas earlier machines were made of wood. The key factor in the iron industry was the heating process and the hammering of smelted iron, both of which depended wholly upon water power.

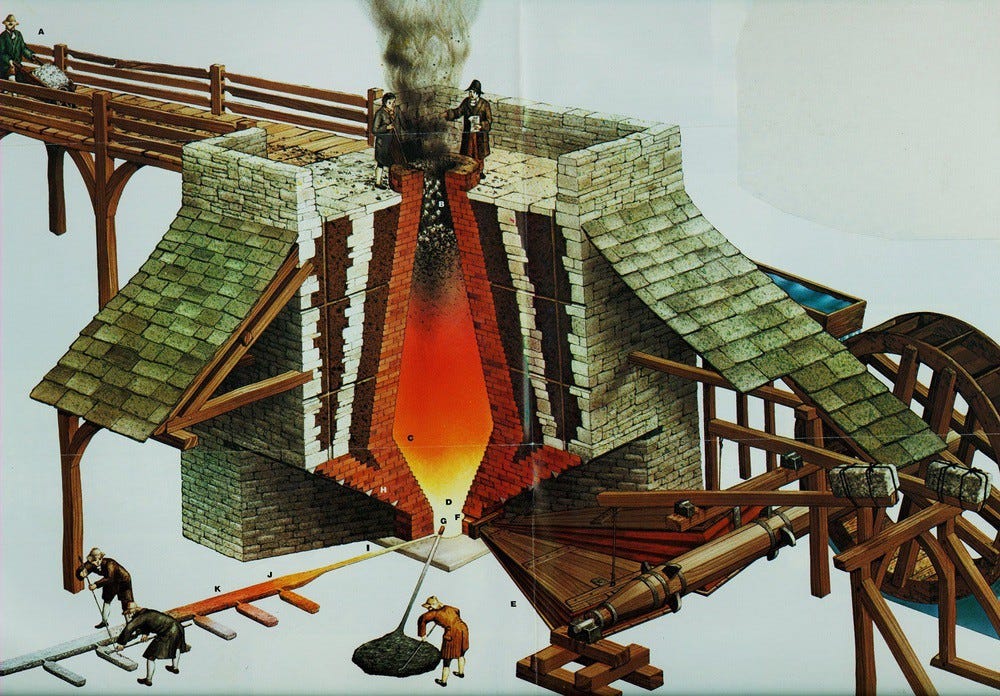

Without water-powered bellows, it would simply not have been possible to produce temperatures in the blast furnaces high enough to produce cast iron economically. This water-aided furnace technology was an essential element of the iron industry and its high output. The iron industry depended on water power to produce the new machines of the new industries, such as rolling mills, metal lathes, and hydraulic hammers, which again required water power.

It is therefore safe to assert that the increase in productivity was dependent upon more efficient use of water, in this industrial sector as in other emerging industrial sectors at the time.

So what exactly is a water-powered bellow? Rather than squeezing air out of a bellow with your hands a giant water wheel would do the job. This allowed blast furnaces to use bellows much larger than a human could operate. Men dump iron ore and charcoal down the top.

Without these water-powered looms you simply cannot produce steel and iron in quantities and quality needed to build steam engines and railroads, so crucial to the industrial revolution in later stages.

So Brits Were Geniuses By Using Water Power?

People like to flatter themselves for past success by believing in exceptional qualities such as ingenuity and intelligence.

However there was nothing exceptional about using water-power to drive machinery. It was widely known in the rest of the world. In fact power-power originated in China and got brought to Britain through the Roman Empire (page 43):

However, the development of the overshot system was crucial for the industrial breakthrough. Technologically, the equipment in itself was not revolutionary, and it would probably not have puzzled or surprised a millwright from medieval China or parts of the Ottoman Empire. Many of the early water-powered cotton factories were converted silk mills, which themselves were often converted medieval corn mills, pointing to the long and varied history of water-powered technologies.

One crucial invention of the Industrial Revolution was multi-spindling spinning machines. What do I mean by a multi-spindling machine? The picture below illustrates the concept:

Normally a single human would work with a single spindle to turn yarn into thread. The invention of machines like Spinning Jenny made it possible for one person to spin multiple threads at the same time.

The Spinning Jenny however was just a first step, as it required a person to crank it. Richard Arkwright improved upon this idea with a multi-spindling machine called the Water Frame powered by a water wheel.

However while people like Richard Arkwright are famous and secured themselves a permanent position in the history of the Industrial Revolution, what they did was in fact not new.

The Chinese had yet again beaten Britain by hundreds of years. Already in medieval times, the Chinese had something equivalent to the water frame (Terje Tvedt page 45):

It has been documented that a water-powered multi-spindled spinning machine was in use in northern China by the end of the thirteenth century.

Then why didn’t the industrial revolution start in China? A mundane fact explains why: Chinese rivers are poorly suited for driving water wheels. British rivers, in contrast, are among the best suited for this task, especially the ones around Manchester.

Since they knew the technology, the Chinese had the scientific and engineering capability to build reservoirs and dams, but they could not sufficiently regulate the extremely variable flow on a year-round basis, which this new kind of industrial production required to be profitable. Furthermore, the reservoirs soon filled with silt. The Chinese water system was extremely difficult to use for regular industrial production given available technology at the time, and therefore Chinese factories lacked a regular power supply that could transform them into modern machinery-based workhouses. There were very few exploitable water resources close to where iron was found and made

China unlike Britain did not have a lot of areas offering sufficient water pressure to drive water wheels, what we call hydraulic head. As explained by Tvedt page 46:

On the extremely flat Yangtze plain, crossed by a violent, silt-laden river, draining 70– 80% of China’s precipitation, there were very few appropriate places to exploit the flow of water for driving water wheels, especially overshot vertical wheels. The Yangtze and its main tributaries could not be used for producing power through numerous water wheels, in the way that the much smaller and more modest English rivers, streams, and brooks could. In major cotton-producing regions, there was simply not sufficient head of water to work hydraulic machinery. Successive floods also functioned as major disturbances influencing the dynamics of the river–land interface, and human–water relations made factory establishment on the river banks virtually impossible.

The Italian Connection

It is also interesting to note that Britain wasn’t even first in Europe in using water-powered machinery for textile production. The Italians had begun far earlier using machinery, even water powered machinery to throw silk:

In 1700, the Italians were the most technologically advanced throwsters in Europe and had developed two machines capable of winding the silk onto bobbins while putting a twist in the thread. They called the throwing machine, a filatoio, and the doubler, a torcitoio. There is an illustration of a circular hand-powered throwing machine drawn in 1487 with 32 spindles. The first evidence of an externally powered filatoio comes from the thirteenth century, and the earliest illustration from around 1500

In fact the first water powered textile factory (silk mill) in Britain setup in Derby was directly derived from Italian technology and design.

The Italians were the first to build mills that contained anything more than a set of spinning wheels. Thomas Cotchett’s mill, was built in Derby in 1704, and was a failure. John Lombe had visited the successful silk throwing mill in Piedmont in 1716, an early example of industrial espionage. He returned to Derby with the necessary knowledge, with details of the Italian silk throwing machines — the filatoio and the torcitoio — and some Italian craftsmen.

Thus the next question would naturally be, why did the Industrial Revolution not happen in Italy? Italy was in many ways among the most advanced countries in Europe ever since the Renaissance began there.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Erik Examines to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.